April Market Pulse – taking risk in unprecedented times

The reward for taking risk is usually how investors grow their portfolios over time. Chris Godding explains its principal components: inflation, dividend, premium and real growth

The value of investments can fall as well as rise and that you may not get back the amount you originally invested.

Nothing in these briefings is intended to constitute advice or a recommendation and you should not take any investment decision based on their content.

Any opinions expressed may change or have already changed.

Written by Chris Godding

Published on 29 Apr 202011 minute read

Our investment philosophy is built on a desire to preserve and grow the real value of wealth over time and I am going to use these goals as a framework for this month’s piece.

While we cannot guarantee that portfolios will never fall, my approach to preserving wealth has always been to seek downside protection through a combination of valuation and quality.

History is littered with external shocks like Covid-19 and they have two things in common. They are always different and, by their very nature, unpredictable, which means insulating a portfolio to eliminate all the risks would essentially result in reducing the portfolio return to the risk-free rate, which currently is just above zero. Therefore, we aim to build portfolios that maximise the return for an acceptable level of risk where the fundamental value of high quality assets provides protection and growth over time.

By sticking to this principle, we can be confident that dislocations in market pricing are likely to be temporary while, in contrast, a low-quality and over-valued asset offers no such comfort. This focus on quality and valuation discipline is how we select the funds and how we build portfolios, looking in detail at the underlying holdings, checking the consistency of the investment philosophy of the managers and constantly reviewing the long-term premium we are being paid to take the risk of investing in an asset class.

Occasionally, we are rudely reminded by events like Covid-19 exactly why we get paid that premium, but the golden rule of investing is to keep compounding it over time. To an extent, this reward for taking risk is how investors grow their portfolios over time and it is made up of four principle components in the form of inflation, dividend or coupon, valuation discount or premium and real growth.

In all honesty, knowing the value of each of these components in the short term is difficult at the best of times and, in current circumstances, nigh on impossible. Assuming equilibriums are restored over time, patience is usually an ally in such conditions, although it would be naïve to assume each component will be unaffected and a constant.

The current disruption to global GDP growth, the extent of the demand shock and the response by central banks and governments is of a scale I have not seen in my 35-year investment career. Comparable in scale only to the Great Depression and the Second World War, the assumptions that were valid just two month ago are likely to be fundamentally flawed.

As we learn more over the next few months, we will revise these assumptions accordingly but to say we have clarity today would be mendacious. Each element of long-term dividends, valuations and sustainable growth are worthy of a thesis of their own and we will cover our conclusions in future publications. For the moment, our working assumptions are as follows.

Inflation

While inflation is notoriously difficult to forecast, given the volatility of the independent variables such as commodity prices, currency exchange rates, output gaps and money supply, our base case for the forecast horizon out to the end of 2021 is that we continue to expect deflation to be more of a threat than inflation.

This is driven by the quantum of the output gap and the under-utilisation of labour and assets which will keep wages and pricing power under pressure. Shelter, measured in either rents or mortgage costs are also likely to fall or remain stable, while healthcare costs, which make up a fair proportion of the inflation component in the developed world, are likely to rise.

From a global perspective, the depreciation and appreciation of currencies should result in equilibrium but on balance the monetary and fiscal policy shift in the Western economies imply weaker currencies and a relatively higher inflation impulse compared to Asia.

However, the higher debt burden and demand shock mean that it seems prudent to pencil in a 50% cut in the inflation component to just 1% per annum compared to our historic long-term forecast of 2%. In the longer term, once we have closed the output gap, inflation may be more of an issue. However, it is important to remember that debt and inflation are not good bed partners as various emerging markets have shown in the past, so it is likely that the central banks will use the extensive weaponry at their disposal to contain it if it should become an issue.

Dividends

Again, a subject worthy of a piece on its own, the conclusion for dividends on a global scale is that we are factoring in a 30% cut in pay-out ratios through to the end of 2021 before returning to more normalised levels over a ten-year horizon. Based on current equity prices and our forecast for equities over the next 18 months, this would imply a global equity dividend yield of around 2%.

One notable exception to this picture would be the UK where the historic pay-out ratio for the large cap companies, which has been in excess of 100% of earnings, is being cut aggressively in order to preserve cash flow or as a result of government assistance (and insistence).

Our base case for the UK is that many companies may find this an opportune moment to cut their pay-out ratios permanently toward more efficient levels. Therefore, we would not be surprised to see dividend yields fall from 5.5% on the MSCI UK today to around 3.5% longer term. Although this represents a significant cut in income, the flipside is that the retained cash flow can be reinvested and add to growth in what should be a more efficient allocation of capital.

For various tax and incentive-based compensation reasons, American companies have tended to use more of their earnings to buy back stock than to pay dividends. This shrinking equity dynamic has been a key driver for US equity performance and we expect it to fade away quite dramatically over the next year if dilution from equity based compensation continues to be used in place of cash bonuses.

With regard to UK bonds, our outlook on interest rates and inflation suggest little change in total yield compared to recent history, with low government bond yields and wider credit spreads compared to pre-Covid 19 levels for some time to come. Having spoken extensively to the managers of our preferred bond funds, we have added to investment grade corporate bonds in our centrally-managed portfolios post the recent sell-off to take advantage of the wider spreads being offered in the market compared to gilts.

Valuations

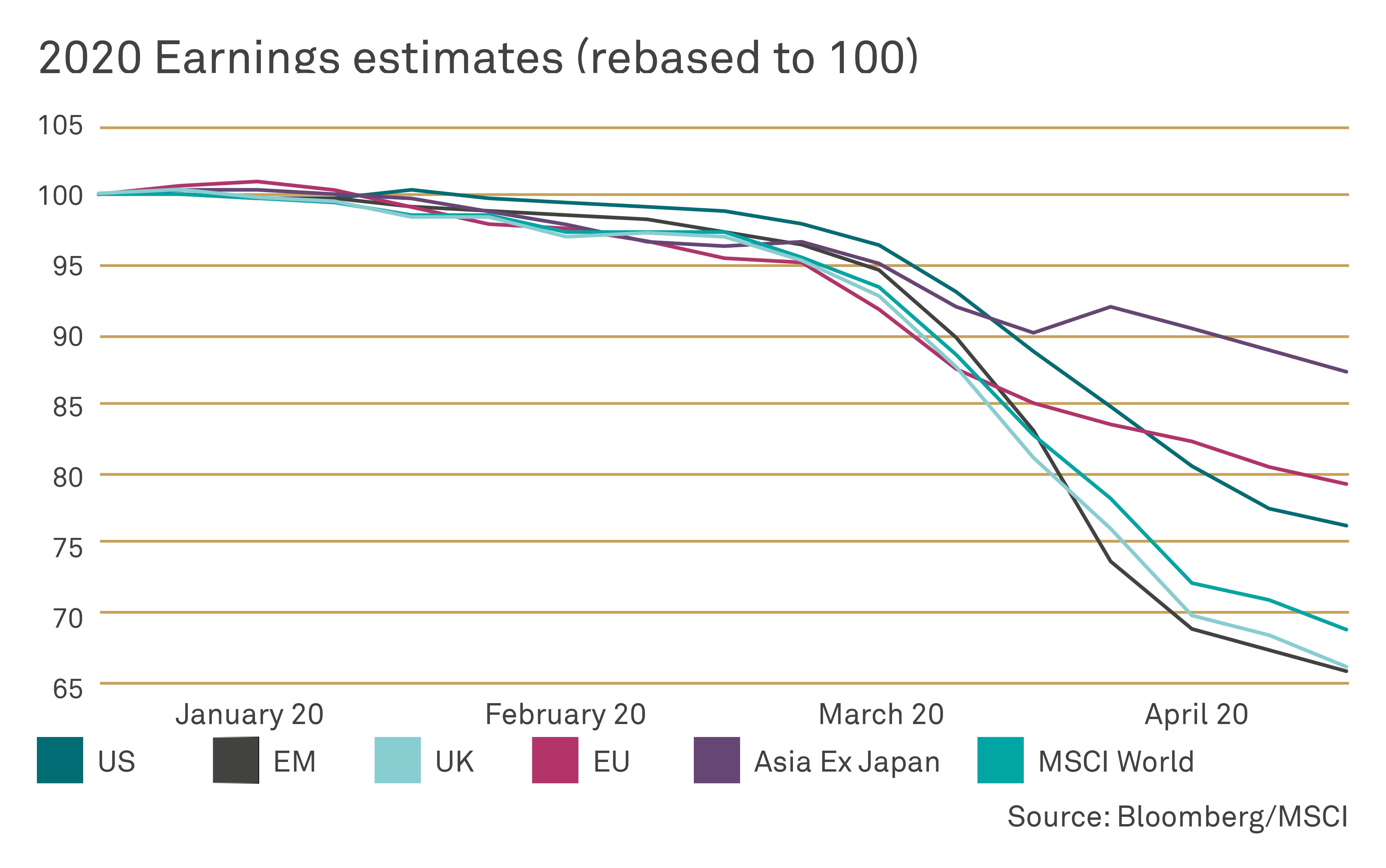

I seem to be changing the Y-axis on my 2020 earnings estimate chart every week at the moment, along with the chart of the oil price!

Equities are a long-duration asset and it would be wrong to value them just on near-term earnings. However, given the scale of revisions and the significant short-term unknowns it is probably best to look at alternative fundamental valuation metrics such as the Shiller Cyclically Adjusted P/E (CAPE) and book value. Using these metrics, global equities are about 10% below the long run average CAPE and in line with the average when using price to book, leading us to assume that over the longer term, the valuation bias is supportive of equities, but not materially so.

On a regional basis, there are some interesting outliers with the UK, the Eurozone, Japan, Australia and Hong Kong looking very cheap using CAPEs and equities in Germany, Hong Kong and Japan when using price to book. A preference for UK equities in our portfolio has hurt performance this year but our favoured managers have done an excellent job in beating the market and, based on valuation, we are going to stay the course.

The US is now around fair value on both our preferred measures, having been quite overvalued for some time, but superior returns on capital at the biggest companies in the index suggest that the US has long-term appeal. The money being printed at the Fed will eventually find its way around the world but, in the near term, the US economy is likely to be the key initial beneficiary and we need to bear this in mind and not be too negative.

In summary, the key message is that we believe equities are marginally cheap overall, but in some markets the opportunity for valuation appreciation is significant. The huge government stimulus packages and increase in money supply also raise the probability of an overshoot, but we are probably more conservative on that assumption than the current consensus.

Although the stimulus seen so far is indeed massive by historical standards, it is not the level but the excess of money supply that drives financial assets higher. In this crisis, we suspect that the real economy will absorb a substantial proportion of the stimulus, leaving less excess than we experienced post the GFC, when a collapse in consumer confidence and a contraction in bank leverage ratios pummelled the demand side of the economy.

Central banks printed money but nobody wanted it and the excess went into the stock market and real assets. It took a decade for the global economy to return to full employment and real wages to grow again, while financial assets boomed. The current situation is quite different in that there will be a significant increase in the demand for money once activity re-starts. The real economy will absorb much of the additional capital available and over the coming years, fiscal austerity will be replaced by a rebuilding of the critical infrastructure that has clearly become inadequate.

I suspect that this rebuilding will leave less excess for financial asset inflation than investors currently anticipating the GFC playbook expect. In recent weeks, the prospect of ending the lockdown and the open-ended support from governments and central banks has led to a recovery in equities.

In the short term, we are more inclined to think that investors may be a little ahead of their skis but looking further forward, our work suggests that equities have approximately 20% potential appreciation through to the end of 2021. It is also heartening to hear that our managers, who we speak to on a regular basis, see compelling opportunities in the high-quality companies they invest in.

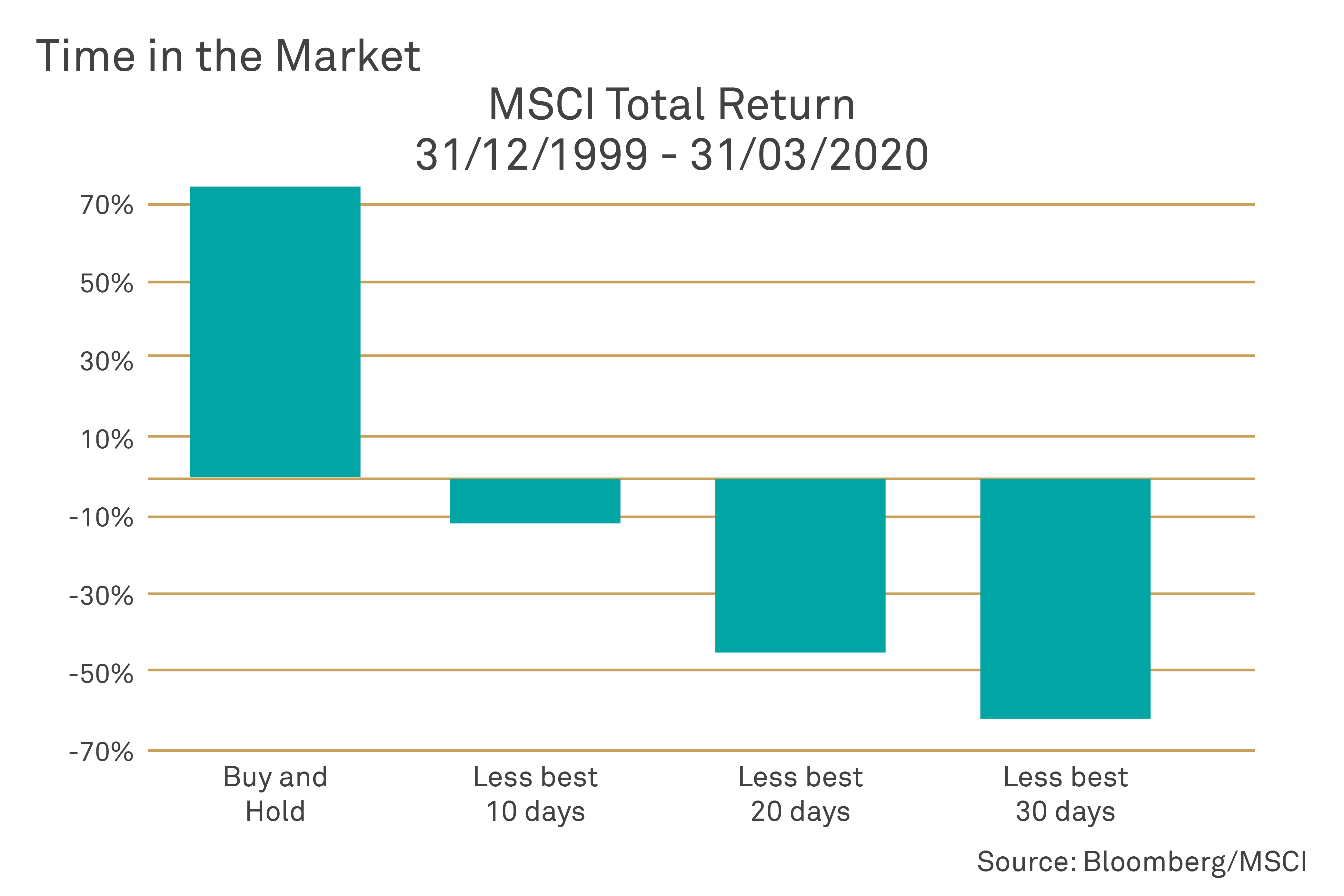

We chose managers because they are investors in companies for the long term rather than traders. Of course they will re-examine their thesis in the face of a macro shock, but they tend not to be materially influenced by unpredictable short-term events. They are more interested in the competitive advantage, sustainable free cash flow growth and superior returns on capital employed, knowing that these qualities will drive performance and growth in the longer term. These managers make up a critical component of our preserve and grow philosophy: we are very selective in who we choose and are reassured by their consistent focus on quality over recent months. In terms of preservation of capital, we held our ground during the worst of the recent sell-off in equities and our portfolios have fully participated in the subsequent recovery, reminding us once again that it is the time in the markets, not the timing itself that is important.

The statement tells us there's benefit in compounding risk premium over time and not to over-trade. It does not prevent us from taking advantage of dislocation with tactical changes to the portfolio at extremes like we did when we topped up our equity weights in the managed funds back to target near the lows of late March. It simply reminds investors that the usual emotional reaction is to do the wrong thing at the wrong time.

The chart below clearly shows the negative effect of missing out on the best days in the market which usually come after some of the worst when people are driven to panic.

Investors who sold out near the lows we saw in March have ‘locked in’ their losses and now face the painful decision of whether to bite the bullet and buy back over 20% higher.

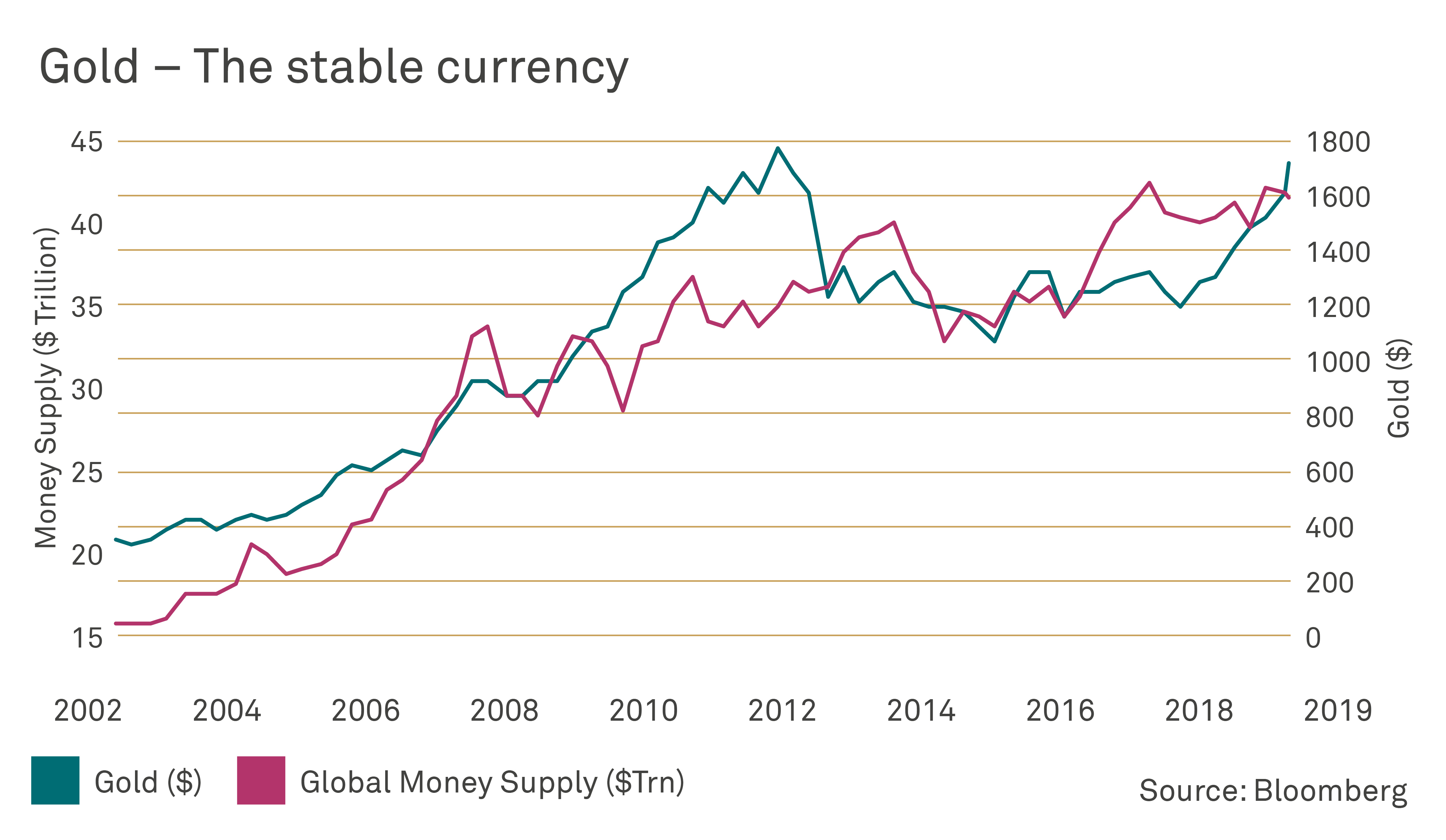

Gold is another form of wealth preservation in real terms; we became more positive and added to the position in our managed portfolios when we saw the extent of the monetary stimulus across the developed world. We view gold as a pseudo-currency which is made, or more accurately, mined, at a slow and steady pace.

In the meantime, the printing presses at the Fed and other central banks are doing overtime. According to Deutsche Bank, the size of the bailout for Covid-19 by the G7 is approximately US$11 trillion and debt to GDP is expected to rise 30%, leaving it at 300% of GDP. It is the largest bailout in history and compares to a total of US$7 trillion by the Federal Reserve in QEs 1, 2 and 3 from 2008 to 2012. Fiat or paper currency must, in our view, be worth less over time as a result of this prolific supply and the price of gold should benefit.

During the QE phase from 2008-12, the gold price rose by 92% and since the beginning of this year it is up just 12%, which implies there is a lot more to go.

Gold is a good example of an alternative source of return with asymmetric risk return characteristics. We may be wrong, of course, but in our view the evidence and historical experience suggest that the probability of being right is heavily skewed in our favour.

Clearly, the macro and micro economic picture will be in a phase of significant adjustment for quite some time, and hopefully this piece gives you a clear view of how we are taking the information and fine-tuning our assumptions. Similar to driving in fog, clarity is in short supply and dramatic moves would be dangerous, so we tend to be focused on reaching our longer-term goals as opposed to ending up in a ditch.

For more information or if you have any questions, please get in touch by calling 020 7189 2400 or book a telephone appointment.

Get insights and events via email

Receive the latest updates straight to your inbox.

You may also like…

Market news

2024 Autumn Budget Overview: The key announcements from Chancellor Rachel Reeves

Market news