A better outcome for income?

Income shares have experienced underperformance recently, but is a revival for income investing on the horizon? Our article explores this

The value of investments can fall as well as rise and that you may not get back the amount you originally invested.

Nothing in these briefings is intended to constitute advice or a recommendation and you should not take any investment decision based on their content.

Any opinions expressed may change or have already changed.

Written by Tom White

Published on 20 Sep 20225 minute read

Equity income investors have been through a tough time. In what was until recently a prolonged bull market for equities, dividend-paying shares were consistent laggards. Over the 10 years to December 2021 the MSCI World Index of global equities rose by +300.5% [1]. The MSCI World High Dividend Yield, its income-focused cousin, was up just +189.6% [1] over the same period.

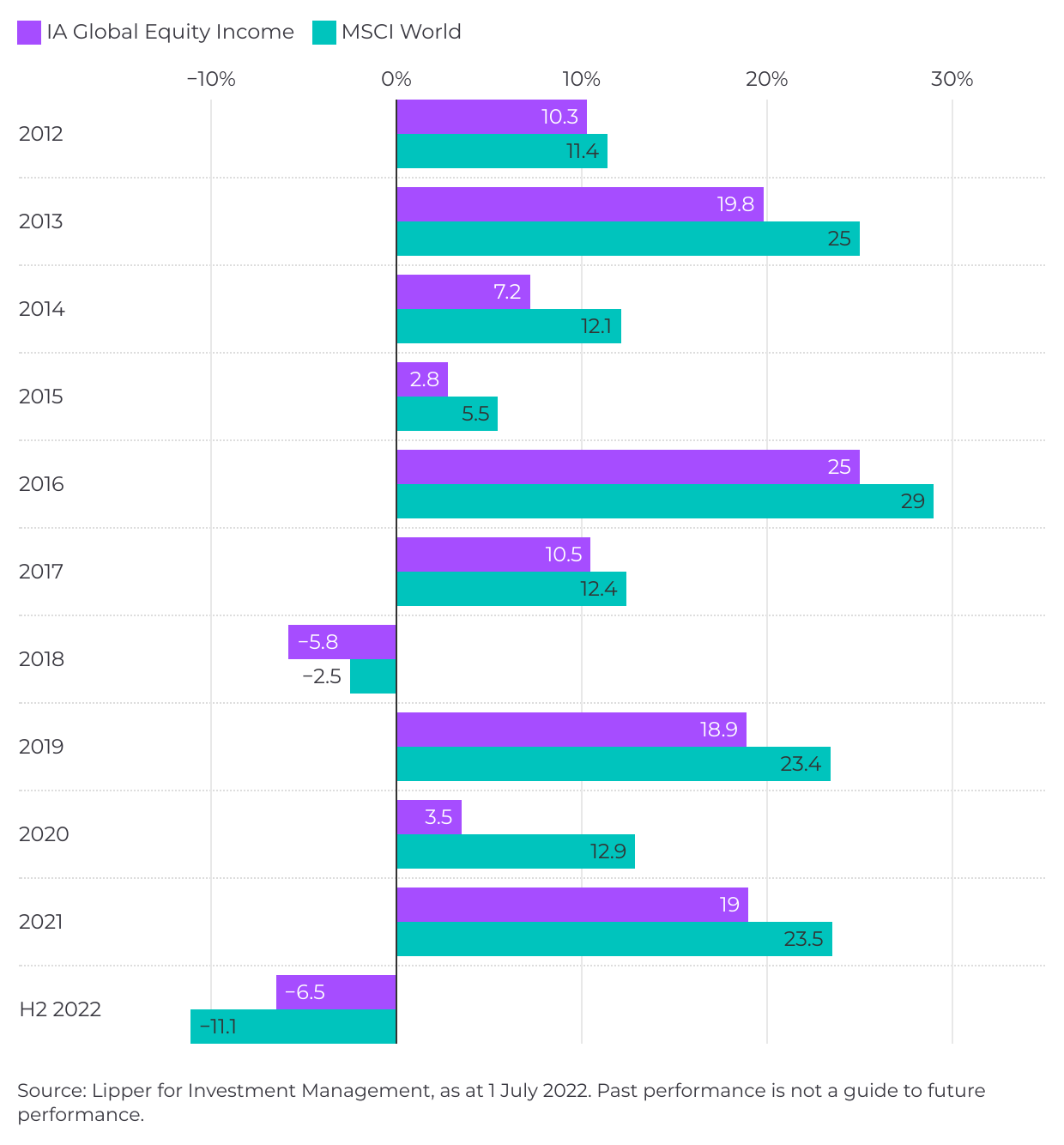

This performance has been reflected in the funds that invest in those income-paying shares. The IA Global Equity Income sector, a composite of global income funds, underperformed global equities generally in every calendar year from 2010 to 2021 [1].

To make matters worse, the performance slump has come while global funds generally have been booming. A new generation of more growth-focused fund managers have been either agnostic to dividends or actively hostile to them, with the likes of Fundsmith Equity captivating investors and delivering benchmark-beating returns. Income investors looked on enviously.

However, this year the story has been different. Income funds have provided a degree of resilience in 2022’s turbulent markets, while Fundsmith and its many imitators have struggled. So are we at the start of a resurgence for income investing? To understand that we need to look at why income shares were lagging in the first place.

Global Equity Income sector – performance versus global equity benchmark

Why have income funds underperformed?

There are two key reasons for the underperformance:

The technology boom. Companies typically go through a life cycle. Newer, faster-growing businesses don’t tend to pay dividends, preferring to invest their profits to fund further expansion. Once they’ve grown, investment opportunities become more limited, so they instead start to pay out their profits as dividends.

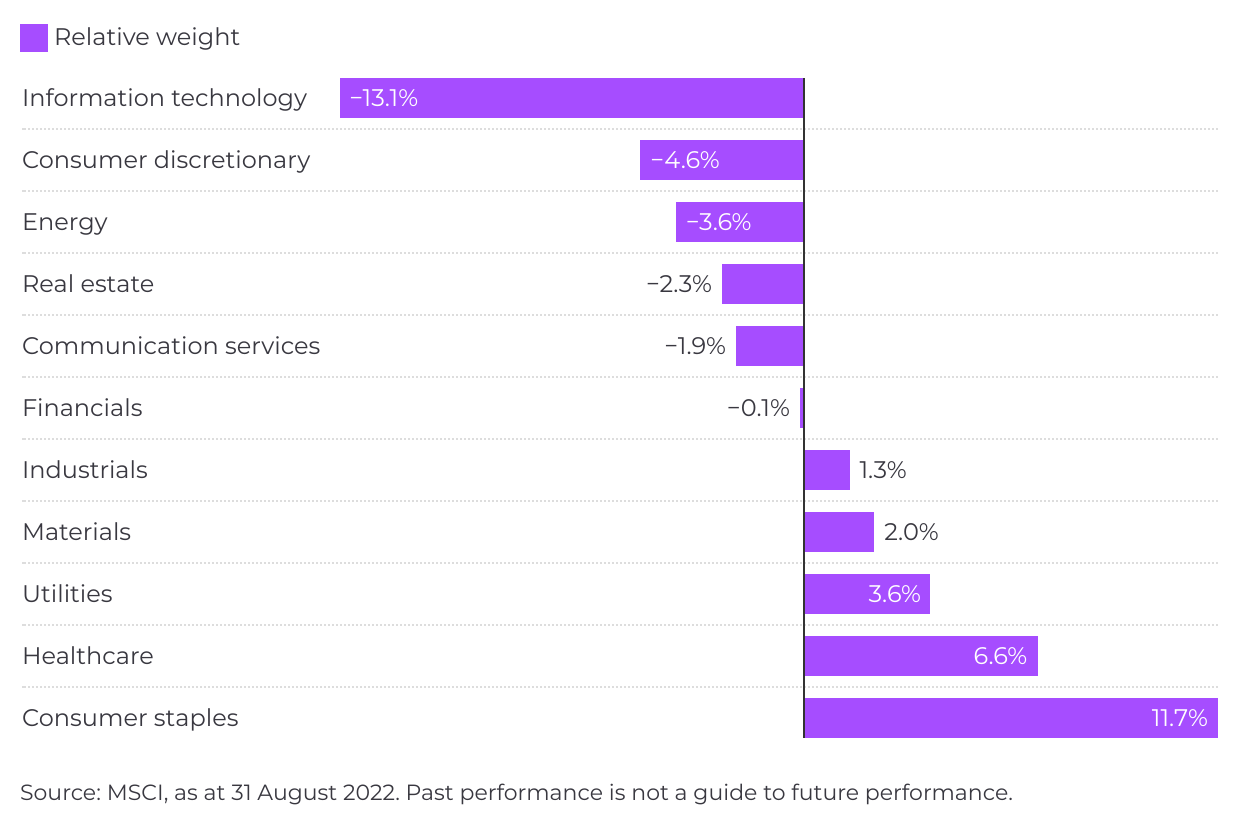

This means that, broadly speaking, income-paying companies are more mature, larger and slower-growing. They also tend to be found disproportionately in certain industries, notably consumer staples, healthcare and utilities. In contrast, dividends are less common in the information technology and consumer discretionary sectors.

MSCI World High Dividend Yield – sector weights relative to MSCI World

These differences mean that, at times, dividend-paying companies can perform differently to the market. In recent years they’ve performed very differently. What was different this time is that the stock market’s rise was heavily fuelled by technology companies. And thanks to a combination of technological innovation and globalisation, some of those companies have been able to sustain their growth for much longer.

Alphabet, Amazon and Tesla reached trillion-dollar market valuations and still don’t pay dividends. These companies are also US-based, and US companies have less of a dividend-paying culture than those elsewhere, favouring buybacks of shares instead. Dividend-payers in more stable, mature industries simply couldn’t keep up.

Low interest rates. Most of us are familiar with the ‘miracle’ of compound interest, for example: if interest rates are at 5%, £1,000 compounds into £1,712 over 10 years, but if rates are at 0.5% it grows to just £1,051. Less familiar is that this effect works in reverse, to calculate the present value of future returns. Again, if interest rates are at 5%, £1,000 in 10 years’ time is worth £584 today, but rates at 0.5% would be worth £951.

Analysts use this maths when valuing companies. And the ultra-low interest rates put in place following the 2008 financial crisis meant that future returns became almost as valuable as present-day returns. This tilted the balance away from companies producing profits and dividends in the here and now, and towards fast-growing companies. Their share prices shot up.

So not only were technology companies growing more quickly, but investors were prepared to pay a higher price for that growth. In some cases that growth wasn’t far away. However, in recent years a lot of investment has gone into highly speculative companies with little in the way of profit or revenues, let alone dividends.

What has changed?

Interest rate rises. 2022 has seen a flurry of interest rate rises as central banks rushed to put a lid on rising inflation. The US Federal Reserve and European Central Bank have both upped rates, the latter for the first time since 2011, while closer to home the Bank of England has increased rates from 0.25% to 1.75% [2], Further rises are expected.

Slow growth. 2022 has also seen economic growth slow down and in some cases go into reverse, with major economies including the UK on the brink of recession. While most share prices have been hit, the slowing economy has had a particular impact on companies whose valuation is dependent on their future growth, most notably technology companies, as the market questions to what extent this growth will now materialise.

In some cases it will – the world isn’t about to throw away its smartphones any time soon. However, in other cases there is a growing risk that it won’t – Netflix recently reported a first ever decline in its subscriber numbers.

Against this backdrop it’s not surprising income-paying companies have held up better. Broadly speaking they are less reliant on future growth as their profits are already here.

Will income stocks’ outperformance continue?

The short answer is that it might already have stopped - growth stocks have shown signs of a comeback in the second half of 2022. We believe if their outperformance resumes and markets rise, income shares are likely to lag. However, it’s worth remembering that even if they do, they could still deliver reasonable returns – even in its decade of underperformance the MSCI World High Dividend Yield still delivered annualised returns of +11.1% [1].

And if, as many expect, economic growth and stock market returns are more subdued going forward, income stocks could come into their own. Maths is on their side, because when growth is low income becomes a bigger source of returns. If for example, share prices are growing at 20% a year, whether a company pays a 3% yield is slightly academic. When growth is low, that same 3% dividend yield suddenly becomes a bigger and more important part of returns.

The story of the tortoise and the hare has survived for thousands of years, and with good reason. Sometimes the tortoise does win.

Source:

[1] Lipper for Investment Management

[2] Official Bank Rate history, Bank of England [accessed 8 September 2022]

Interested in income funds?

To see our favourite income funds plus funds from across the sectors, download The Best Funds List.

Important information

This article does not constitute advice nor a recommendation relating to the acquisition or disposal of investments. No responsibility can be taken for any loss arising from action taken or refrained from on the basis of this publication.

The value of an investment, and any income from it, may go down as well as up and you may get back less than you originally invested.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance.